Decoding Respiratory Rates: Why ECG-Derived and Visual Rates Don’t Always Match

A common question we receive is why the respiratory rate derived from an ECG signal (EDR) or SpO₂ plethysmography sometimes differs from the rate obtained by visually counting chest movements. The answer often lies in the patient’s state of arousal. Understanding the distinctions between Sleeping Respiratory Rate (SRR), Resting Respiratory Rate (RRR), and rates taken during a non-resting state is crucial for accurate clinical assessment.

Defining the States

- Sleeping Respiratory Rate (SRR): This is the rate measured when the patient is in a natural, deep sleep, completely undisturbed. This state represents the true baseline respiratory drive and is considered the most sensitive indicator for detecting early signs of left-sided Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) in dogs. The ACVIM consensus guidelines endorse client monitoring of sleeping or resting respiratory rates for the early detection of pulmonary edema in dogs with CHF.¹

-

Resting Respiratory Rate (RRR): This is measured when the patient is awake but calm, relaxed, and resting in a stress-free environment (e.g., lying down in the consult room after a few minutes of acclimatization). While RRR is a valuable clinical parameter, it is typically higher than SRR due to a mild degree of environmental awareness or stress.

-

Non-Resting State Rate: This is measured when the patient is stressed, anxious, panting, or moving. This is common during a physical exam. Panting, in particular, involves rapid, shallow breaths that can be difficult to count visually and creates a significant mismatch with physiological signals.

Why the Mismatch Happens: Arousal State is Key

The agreement between a technology-derived rate (like EDR) and visual inspection is highest when the patient is in a true resting or sleep state. Here’s why non-resting states cause discrepancies:

- Pattern Change (Panting vs. Eupnea): In a calm state, breathing is regular (eupnea). EDR algorithms excel at detecting the consistent, rhythmic modulation of the ECG signal caused by normal breathing. During panting, the breathing pattern becomes rapid and shallow. Visually, you may see many small abdominal movements. However, these shallow breaths may not cause significant enough shifts in the electrical axis of the heart or blood volume for the EDR algorithm to detect each one reliably, leading to an underestimation.

- Physiological Noise: In a stressed or active state, muscle tremors, movement artifacts, and an elevated heart rate can obscure the clean respiratory signal within the ECG or SpO₂ waveform. This noise can either mask the true respiratory signal or create false “breaths” in the derived data. Visual counting in a moving patient is also highly subjective and error-prone.

The Clinical Takeaway: When and How to Measure

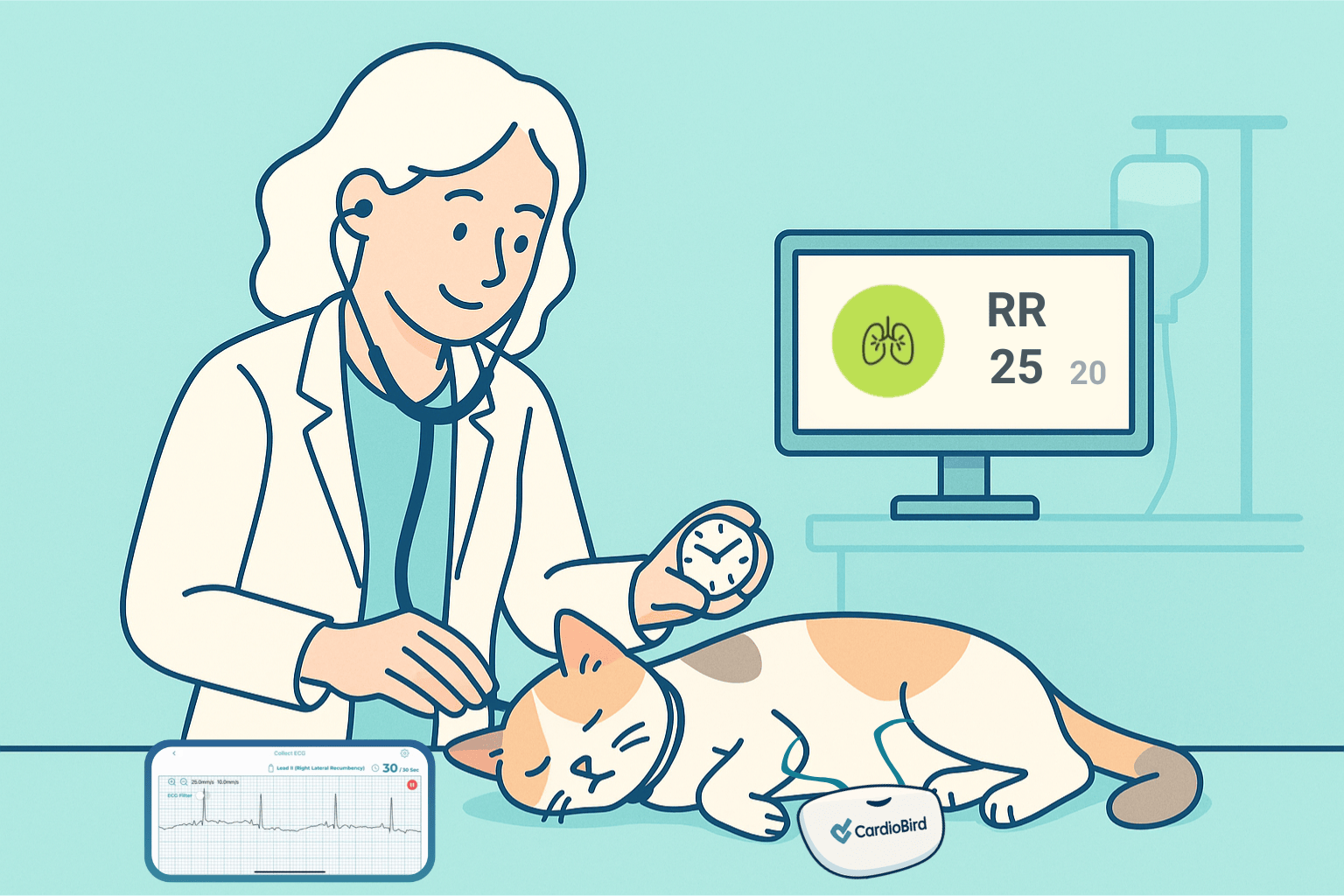

For reliable respiratory rate monitoring in cardiac and hospitalized patients, the patient’s state is paramount.

- For At-Home CHF Monitoring: SRR is the gold standard. Instruct clients to count breaths when their pet is in a deep sleep.

- In the Hospital: Aim for a true RRR. Allow the patient to acclimate in a quiet cage or room for 10-15 minutes before counting. Observe from a distance without touching or disturbing them. Count the breaths over 30 or 60 seconds.

If you see a significant discrepancy between a physiologically derived rate and your visual count, first ask: Is the patient truly at rest? Panting and anxiety are the most common culprits. A rate derived from a high-quality ECG during a calm resting state is typically very reliable. However, any rate—visual or derived—obtained from a panting or stressed patient should be interpreted with caution.

By prioritizing the patient’s state of arousal, we can ensure respiratory rates are accurate, comparable, and meaningful for clinical decision-making.

Reference:

1 Atkins, C., Bonagura, J., Ettinger, S., et al. (2009). Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Canine Chronic Valvular Heart Disease. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 23(6), 1142-1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0392.x